If you've ever looked at a build log for a complex project, you know the feeling. It's a wall of text-thousands of lines of dependency resolutions, compiler warnings, and progress bars. Somewhere in there, a missing header file is hiding, but finding it is a chore.

At work, we've been building AI-Harness (part of the broader Rebel

ecosystem), a tool designed to autonomously fix these build failures. While

Rebel acts as a reproducible environment manager for bioinformatics, handling

the mess of apt, conda, and pip dependencies—, AI-Harness` is the

"self-healing" layer.

Our immediate goal was to seed a database of missing dependencies: essentially mapping specific compiler or linker error messages to the exact system packages required to fix them. The idea is simple: feed the log to an LLM, and let it figure out what’s missing. But there's a catch.

The "Lost in the Middle" Problem

Modern LLMs have massive context windows, but they aren't magic. Research like "Lost in the Middle" (Liu et al., 2023) shows that models follow a U-shaped performance curve. They are great at remembering the beginning and the end of your prompt, but they get "lost in the middle."

When you dump a 1MB log into a prompt, the actual error message often ends up buried right in that middle-zone. The model loses its reasoning capabilities, and instead of a fix, you get a hallucination or a generic "I don't see any errors."

Signal vs. Noise

To solve this, I implemented a preprocessing pipeline that uses TF-IDF and Cosine Similarity to find the most relevant chunks of the log before the LLM even sees it. This is a technique I've previously used for this blog's recommendation system, and it turns out to be just as effective for log analysis.

The logic is essentially a mini-search engine:

- Chunking: We break the log into 10-line windows.

- TF-IDF: We rank terms so that common noise (like

building,at,the) is ignored, while rare "signal" terms (likeSegmentationFault,AttributeError, orundefined reference) are prioritized. - Cosine Similarity: We compare each chunk against a targeted query:

"error failure exception traceback".

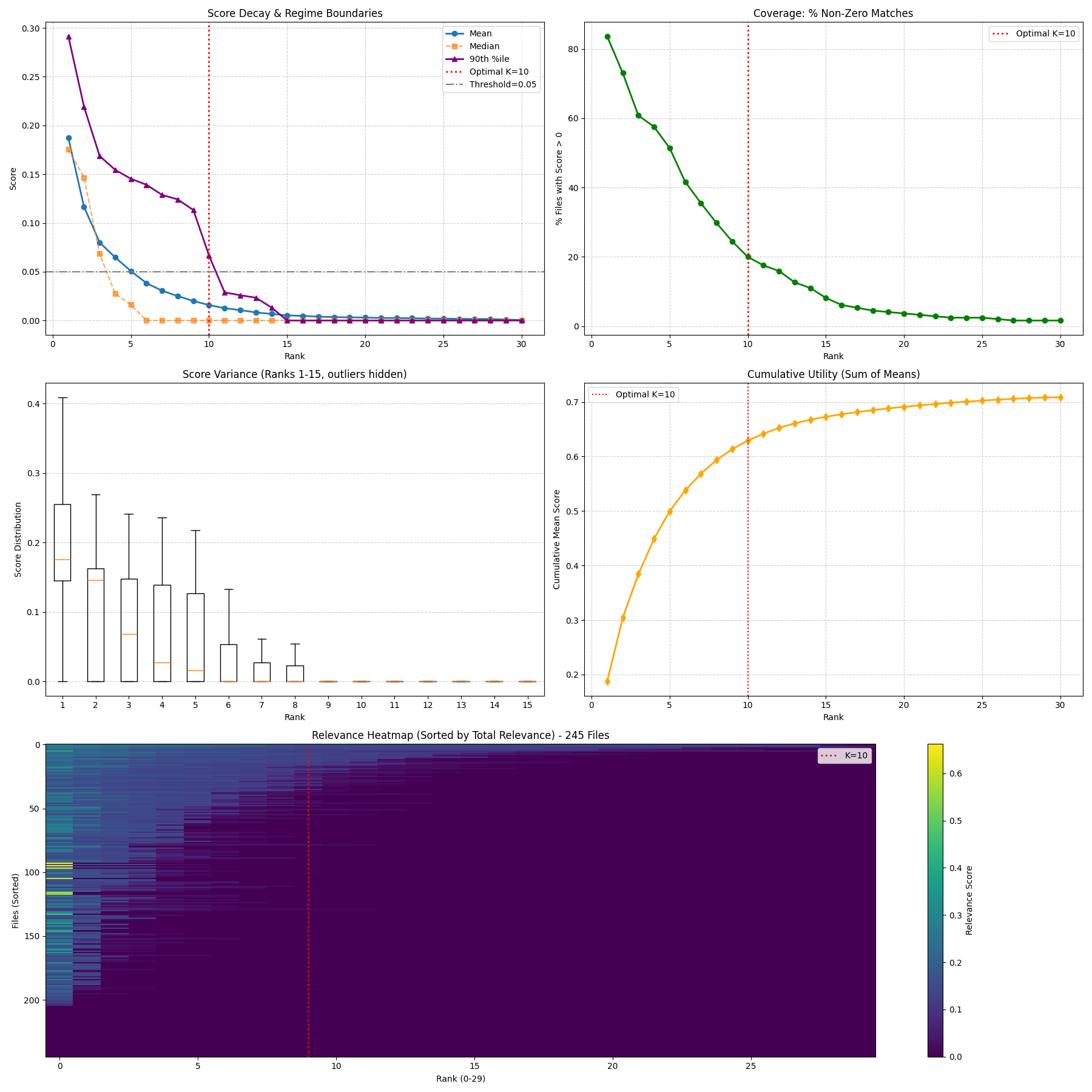

Instead of giving the LLM the entire log, we give it the top K=10 chunks that mathematically look most like an actual failure. We arrived at this number after running a series of experiments to find the "elbow" of the success rate curve—at 10 chunks, we maximize signal without overwhelming the context window.

Does it actually work?

We tested this against a dataset of 245 failed dependency installations from the CRAN (R) ecosystem. The results were pretty stark:

| Configuration | Success Rate |

|---|---|

| Raw Log | 38.0% |

| TF-IDF | 74.3% |

By being selective about what we show the model, we effectively doubled the success rate. It turns out that even for "intelligent" models, less is often more.

If you are interested in the math or the implementation, the project lives over at Rebel and AI-Harness. It's a reminder that even in the age of LLMs, classic Information Retrieval techniques still have a lot to teach us about building the robust, reproducible environments that open science requires.